6 Shocking Train Station Murders That Made Headlines

By Zaituni Amir

Train stations, often bustling with travelers and commuters, have occasionally been the backdrop for some of the most chilling and notorious train station crimes in history. From brutal assaults to calculated murders, these incidents have not only shocked the public but also left lasting scars on the communities affected. These seven shocking train murders, each with its own harrowing details, serve as stark reminders of the dark side of our transportation networks.

1. The First Railway Killing in Victorian England

As railway travel grew popular, luggage thefts and violent robberies became common. The first British railway murder did not occur until 1864, and it was one of the most sensational crimes of the century.

On July 9, 1864, two bank clerks entered an empty first-class carriage and noticed blood. They called the guard who examined the compartment and found blood all over the cushions and the off-side door. Later that evening, the driver of a train heading in the opposite direction noticed something between Hackney Wick and Bow Stations. He stopped the train and discovered an unconscious, severely injured man.

The victim was 69-year-old Thomas Briggs, a bank chief clerk, who later died from his injuries. Briggs boarded the 9.45 p.m. train at Fenchurch Street for Hackney, but the train arrived without him. Instead, a blood-soaked compartment was found with his bag, stick, and a crushed hat that wasn't his. Passengers in the next compartment noticed blood stains on their dresses, likely from blood flying through the window, but heard nothing. Briggs' family confirmed his hat, gold watch, and chain were missing, suggesting robbery as the motive.

The initial breakthrough in the criminal investigation came from a jeweler named John Death. He reported encountering a German man at his shop, who had exchanged a gold chain later identified as belonging to Thomas Briggs. Further investigation led to a cabman identifying Franz Muller, a young German, who had given his daughter an empty jewelry box. When shown the hat found in the carriage, the cabman immediately recognized it, as he had purchased it for Muller. The cabman provided the police with a photograph of Muller. Upon examining the box, the jeweler confirmed it was his and identified the man in the photograph.

A warrant was issued for Muller's arrest, and he was apprehended in New York shortly after departing for the city a few days after the murder. He was found guilty and sentenced to death. Muller was hanged outside Newgate Prison on November 14, 1864.

2. The Infamous 1881 Train Murder Case of Percy Lefroy

On the afternoon of Monday, June 27, 1881, a seemingly routine train ride took a horrifying turn when a brutal murder took place on the 2 o'clock express from London Bridge to Brighton.

It all started when a ticket collector noticed a thin, sickly-looking man in a first-class compartment, covered in blood. The man was hatless, missing his collar and tie, and appeared very distressed.

The man's name was Percy Lefroy. He recounted a harrowing tale to the ticket collector of being attacked by two other passengers who had since disappeared. The ticket collector saw nobody else alight from the compartment but observed that a piece of watch chain was hanging from the man’s boot. Lefroy had, he said, put it there for safekeeping. The platform inspector accompanied him to the local police station, while the ticket collector notified the railway police.

Lefroy filed a formal complaint at the station before being taken to the county hospital for medical treatment. The doctor wanted to detain him, but Lefroy insisted on returning to London for an important engagement. However, he returned to the police station first and was interviewed by several officers. He aroused suspicion, leading to a search where two counterfeit coins were found in his possession, which he denied having any knowledge of.

The carriage where Lefroy claimed the assault happened was inspected, uncovering three bullet marks and extensive bloodstains on the footboard, mat, and door handle. A handkerchief and newspaper left inside were also stained with blood, indicating a violent struggle had taken place.

Despite clear inconsistencies in his story and suspicious circumstances, neither the Brighton Police nor the railway police found it necessary to detain him. However, they remained uneasy and assigned Detective George Holmes to accompany him on a train heading to London.

While Lefroy and Holmes were traveling back to London, a body was found by railway workers on the tracks, miles before Preston Park. The victim was identified as Isaac Frederick Gold, aged 64, who had suffered gunshot and stab wounds. Near his body, a blood-smeared knife was discovered. He had been robbed of his watch and chain and a considerable sum of money.

The news of the discovery was relayed down the line, and at Three Bridges, the station master informed Holmes about the incident. Lefroy managed to escape, and a countrywide search was launched. The Daily Telegraph made newspaper history by publishing the portrait of a wanted man for the first time.

Lefroy was eventually found at a house at 32 Smith Street, Stepney. Bloodstained clothing found in Lefroy's room, along with his prior identification as the person who exchanged counterfeit coins and pawned a revolver, constituted compelling evidence against him. Lefroy was arrested and charged with Gold's murder. He was hanged on November 29, 1881.

3. The Newcastle Train Murder

On the morning of Friday, March 18, 1910, a train departed from Newcastle Station at 10:27 a.m. en route to Alnmouth. Among the passengers was John Innes Nisbet, unknowingly embarking on a journey that would soon take a drastic turn.

Nisbet worked as a cashier for the Stobswood Colliery Company, and on alternate Fridays, he traveled from Newcastle to Widdrington to pay wages at a colliery near the station. On this particular day he carried cash amounting to £370 in a small leather bag. At Newcastle, several people recognized him. Charles Raven saw Nisbet heading for the platform with a man Raven knew by sight but not by name. Colliery cashiers Hall and Spink, who knew Nisbet, saw him walking with a man in a light overcoat and entering the compartment behind them. At the rear of the train, an artist named Hepple, who didn't know Nisbet, saw him pass by with John Dickman, whom Hepple did know. At Heaton, the second station from Newcastle, Mrs. Nisbet usually met her husband briefly before the train moved on. This time, she found him with another man in their compartment.

At Morpeth, a man exited the train and handed his ticket to the ticket collector, who noticed his loose overcoat. During the four-minute water stop, John Grant boarded the train as a passenger. He later testified that upon passing Nisbet's carriage, he saw no one inside.

When the train reached Alnmouth, a porter opened the door of Nisbet’s compartment. Initially appearing empty, the porter discovered three streams of blood across the floor and found a man's body face down under the seat. It was Nisbet, with five bullet wounds to the head. Next to the body were a hard felt hat and broken spectacles.

The Stobswood Colliery Company offered a £100 reward for information on the murderer. Police were given information that Dickman had been seen in the company of Nisbet.

Dickman's detailed account of his whereabouts conflicted with police evidence, leading to him being charged with Nisbet's murder. Blood traces found on Dickman's gloves and trousers presented significant evidence against him during the trial. The discovery of Nisbet's bag, cut open at Isabella Pit, suggested robbery as a possible motive. Dickman admitted knowing about the colliery's payday but denied wearing the mentioned overcoat and stated he had no knowledge of Isabella Pit.

Dickman was executed on August 10, 1910.

4. The Violent Robbery at Ash Vale Station

Transport companies are constantly at risk, particularly those involved in handling both money and goods, which can attract desperate criminals.

In early August 1952, 28-year-old booking clerk Geoffrey Charles Dean lived with his wife and small child in Ash Vale near Aldershot. The family lived a quiet and peaceful life until tragedy struck their small world.

On the night of Friday, August 22, 1952, an ordinary evening took a sinister turn, setting the stage for one of the most shocking train station crimes of the mid-20th century.

At about 7:45 p.m., booking clerk Dean handed over the tickets and date stamps to the senior porter and mentioned he would be working late on his accounts. The porter was the last person to see Dean alive, except, of course, the murderer.

At around 8.45 p.m., a soldier went to the booking office, but found it closed. As he stood there, he heard some shuffling of feet inside the office and what he thought was two voices. He saw the notice stating tickets were issued on the platform after 8pm and went in search of the porter.

At about 8.55 pm, a young junior porter at the station noticed a light was still on in the booking office. Finding this unusual, he alerted another porter and climbed onto the window sill to look inside. Peering through, he saw a man's legs on the floor in a pool of blood, with the safe open. The stationmaster was called, and he ordered the booking office door to be forced open. As he entered, he saw Dean’s body on the floor, face upwards, covered with blood. Dean was fatally stabbed 20 times and £160 was stolen from the office.

Intensive inquiries began, with a police incident room set up in a waiting room at Ash station. They thoroughly checked all nearby hotels and lodging houses. The morning after the murder, two officers visited a lodging house on Victoria Road, Aldershot. In a first-floor bedroom, they found a blood-stained jacket, wallet, and two 10/- treasury notes heavily stained with blood. They waited at the premises to question the owner of the jacket upon his return. Later that night, John James Alcott returned and was arrested; a roll of treasury notes was found in his pocket. Alcott admitted, "That's some of the money," and confessed to the crime. He also disclosed that the knife used in the crime was hidden in his room's chimney. The police discovered the knife in a leather sheath, along with several railway documents. Alcott was taken into custody by the authorities.

Preparing for the Crime

On Monday, August 18, 1952, Alcott told his wife he was going to collect his holiday pay. However, he did not return home, and that was the last time his wife saw him before his arrest. He traveled to Aldershot and stayed the night in a hotel, after purchasing a dagger-style sheath knife. It can be safely assumed that he was already planning the violent robbery he committed four days later. He also visited Ash Vale railway station, where he introduced himself to the clerk, Dean. Alcott visited Dean on several days. One of Dean's duties was to count the money taken by the ticket office before locking it in the station's safe, and it is likely that Alcott was present during one of these counting sessions.

The Verdict

Alcott stood trial on November 18, 1952, where he was found guilty and sentenced to death. He was hanged on January 2, 1953.

5. The Railway Killers

During the mid-1980s, train stations were a place of fear after three horrific murder cases in and around London.

Known as the Railway Murders, the first killing took place on December 29, 1985, when 19-year-old Alison Day was raped, strangled, and her body was dumped in a river near Hackney Wick station in London. It is believed that she encountered her killer after stopping at a telephone box. After being raped, Day tried to escape but was caught by her attackers and strangled with her own clothing.

The horrific series of murders continued with the second taking place in the leafy community of Horsley, in Surrey. On April 17, 1986, 15-year-old Maartje Tamboezer was raped, strangled and her body set on fire. The Dutch schoolgirl had been knocked from her bicycle by a wire that had been tied between two trees. She was then raped, strangled, and repeatedly struck with a rock. The killer then attempted to destroy evidence of the crime by burning Maartje’s body.

The two murders were linked to a series of rapes that had occured happened 1983 and 1985. Multiple women had been raped across London and its suburbs, with most incidents occurring at night near train stations. The police believed the perpetrator responsible for these crimes was the same individual who murdered these two young women.

While the investigation was still underway, the killer struck yet again. Another young woman was killed just a few weeks after Tamboezer’s murder. On May 8, 1986, Anne Lock, a 29-year-old secretary, was abducted, raped,and strangled as she was getting off at the station. She was recently married and worked for London Weekend Television. The murder of the third victim, Anne Lock, sparked the first multi-force police inquiry since the botched Yorkshire Ripper investigation. It was the first such investigation to use basic computers and an early version of HOLMES (Home Office Large Major Enquiry System).

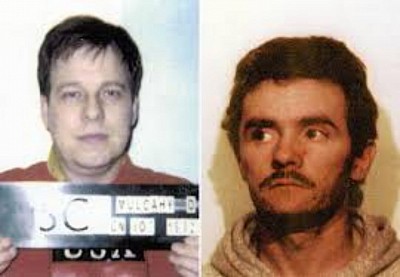

Police started to close in on a suspect, former railway carpenter, John Duffy. He had already been charged with the rape of his estranged wife and had knowledge of the railway system. The officers made a significant breakthrough after he was arrested while following a woman in a secluded park. One of the most vital pieces of evidence against him was a rare type of string called Somyarn. This string was discovered by police in his parents’ house. Evidence against Duffy grew as some of his rape victims were able to identify him.

Duffy went on trial in February 1988. He was convicted of the murders of Alison Day and Maartje Tamboezer, and four rapes, but was acquitted of killing Anne Lock as there was not enough forensic evidence. He was sentenced to a minimum of thirty years in prison.

Although he was now behind bars, the case was far from over. In 1998, ten years after his conviction, Duffy revealed what the police already knew: he had not attacked all those women alone. He disclosed to the police that his childhood friend, David Mulcahy, was his accomplice.

Duffy confessed that Mulcahy had committed the atrocious crimes alongside him and that the two would blast Thriller in their car beforehand to prepare themselves. Following these new claims, Mulcahy was tracked for several months before he was arrested in 1999. DNA tests conclusively proved his involvement in the crimes.

Mulcahy’s trial began in September 2000. Duffy, his former friend, appeared as a prosecution witness against him and gave detailed information about their crimes.

In 2001, Mulcahy was convicted of rape and murder and was sentenced to three life sentences.

6. The Pollokshields Railway Murders

This was one of the most callous and cold-blooded murders ever committed in Glasgow- even by the city's violent standards.

For three railway workers, Monday, December 10, 1945, was just like any other working day. They were on the late shift on that cold December evening at Pollokshields East Railway Station, just off Albert Road, Glasgow. Annie Withers, a clerk, along with clerk-porter William Wright and junior porter Robert Gough, had a busy day, but as evening fell, the station grew quiet.

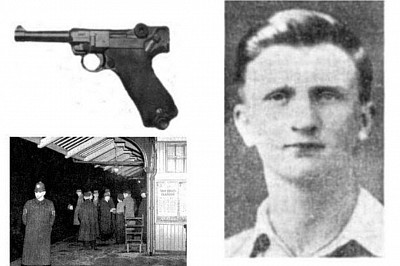

At around 10 pm that evening, all three staff members gathered in the stationmaster's office, around a fire. Suddenly, the office door burst open and a man with a gun appeared in the doorway. All three jumped up and backed towards a nearby desk and Withers began screaming. The gunman fired at Withers, causing her to collapse to the floor in agony. He fired again while she writhed in pain. Turning his attention to 15-year-old Gough, he shot him in the right wrist and then in the stomach, also causing him to fall to the ground. Wright, 42, managed to turn away as the gunman fired at him and the bullet just grazed his body. He lay silently on the floor while the gunman went to the open safe, removed two tin boxes and left the office.

Annie Withers, gravely injured, was transported out of the station to an ambulance. Sadly, she passed away on her way to the hospital. Gough, also seriously wounded, remained conscious during his transfer to the hospital. He later provided a dying deposition to detectives before succumbing two days later. Wright was taken to Glasgow Police Headquarters, where he provided a statement and described the murderer to detectives. He said the killer was about 33 years old, medium height and build, with a thin pale face. He was wearing a light coloured raincoat and brown felt hat.

Detectives and officers were directed to search the railway line and surrounding streets for clues regarding the murderer's escape route and to find the firearm. Unfortunately, the remote location of the railway station and the dark misty night meant that there were no eyewitnesses to his escape.

Based on the cartridge cases found, it was determined that six shots were fired from a 9mm German Luger semi-automatic pistol. A number of fingerprints were also lifted from the stationmaster’s office for comparison purposes. It was later established that a wage packet with £4.3.8d (£4.19p) was all that had been stolen.

Despite having an eyewitness to the murders and substantial forensic evidence, the police did not manage to make an early arrest in the case. As months passed, coverage of the crime faded from newspapers and public interest declined.

In October 1946, police received anonymous information alleging that Charles Templeman Brown, aged 20, possessed a gun. On Wednesday, October 9, Brown learned that detectives had visited his house. Fearing the police had discovered his involvement in the murders, he took the pistol from his bedroom and went out, intending to commit suicide. He tried twice to shoot himself but the gun did not fire.

Filled with panic and not knowing what to do, he saw a policeman on duty, Constable John Byrne. Brown approached the officer and admitted to committing a murder, specifically mentioning it was related to the Pollokshields incident. He then handed over the Luger pistol and box of ammunition to the officer. Byrne contacted the police who dispatched detectives to the scene. Constable George Tytler joined Constable Byrne, cautioning Brown before he spoke again. This caution proved crucial, as while awaiting the detectives, Brown wrote an incriminating letter to a friend on the police box's message pad. This letter was to be damning evidence against him at his subsequent trial. Shortly after, detectives arrived and formally arrested Brown.

Brown went on trial on December 10, 1946. Wright, the surviving railway porter, identified Brown as the man who shot and killed his two colleagues that fateful night.

Key forensic evidence was presented, including Brown’s fingerprints on the safe handle and ballistic evidence from the Luger pistol used in the murders. The focus of legal debate centered on Brown’s letter admitting to the murders, which he had written on a piece of paper in the police signal box.

On December 13,1946, Brown was convicted of double murder and sentenced to death by hanging. However, a successful petition resulted in his death sentence being commuted to life imprisonment.

The story was not to end there; eleven years later, in 1957, Charles Templeman Brown was released from prison. He resumed a normal life, becoming a devoted son to his mother and singing in the church choir. However, eighteen months later, his life tragically ended in a car crash. Brown never provided a reason for the brutal murders of the two railway clerks on that cold December evening. Whatever the reason, Brown died as he had lived – violently.